SO,

LET'S RIDE THE RAILS

The

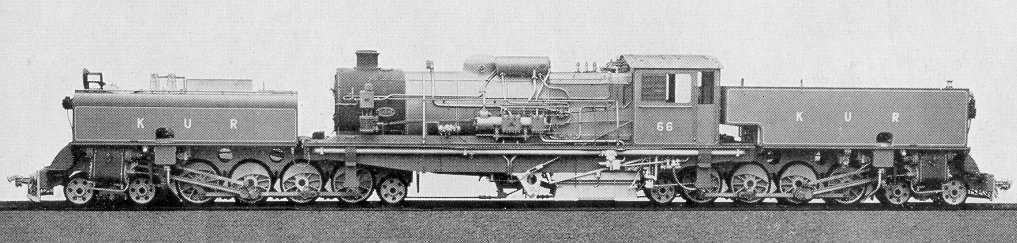

engine in the picture at the top of this page is a Garrett 59 Class Articulated.

This engine was a 4-8-2 by 2-8-4. The livery was the maroon and black with accents

in gold. These engines are considered one of the most magnificent inventions of

the whole steam era because of their mighty look and their great power and traction.

This

engine during my ara was marked "EAR&H" which stands for East African

Railways and Harbours. Under British colonial rule this transportation department

combined all rail and lake traffic in Kenya, Tanganyika (Tanzania), and Uganda.

The engine at the top of the page shows the Garrett with the original "KUR"

markings- Kenya Uganda Railroad. I have a telegraph insulator and a rail spike

marked "UR" (Uganda Railway) which I found on the old line below our

school.

The

video at the upper right is a special train in 2005 with a Garrett engine doing

the Mombasa to Nairobi run.

HERE

IS AN EXCEPTIONAL PAGE ONLINE OF EAST AFRICAN RAILWAYS ENGINES

These

engines, when freshened up, were authoritative and classy to look at. Nothing

said, "The British are coming" like a Garrett steam engine. They were

driven by both White British engineers and Sikhs from India. The Sikhs were very

clever at anything mechanical, and they were obsessive about keeping rules and

polishing their toys. Other Indians were great merchants and financial gurus,

but the Sikhs were the only ones to drive a train and make us feel safe.

These

engines, when freshened up, were authoritative and classy to look at. Nothing

said, "The British are coming" like a Garrett steam engine. They were

driven by both White British engineers and Sikhs from India. The Sikhs were very

clever at anything mechanical, and they were obsessive about keeping rules and

polishing their toys. Other Indians were great merchants and financial gurus,

but the Sikhs were the only ones to drive a train and make us feel safe.

LINK

TO PAGE ON SIKHS IN AFRICA

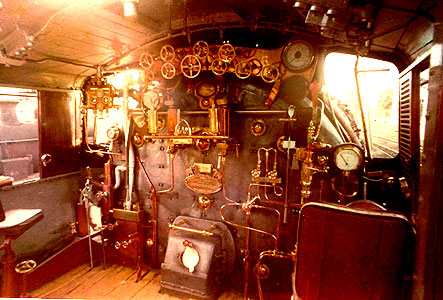

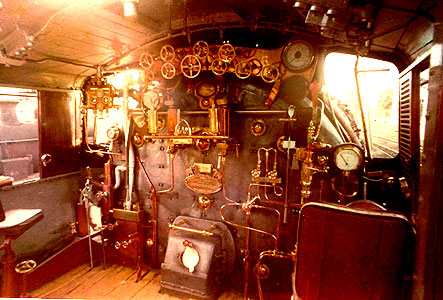

Photo

at left is inside the cab of a Garrett.

The

Garrett was used in other British Empire nations and was a favorite on tight curves

in mountains and on steep grades. The 16 drive wheels under the oil tender and

water tender distributed the drive force well, and the engine could take extremely

tight curves  because

it had a hinge point in two places. The black and white photo at the right shows

the articulation factor saving the day. The switchman threw the track switch before

the engine had completely cleared the switch. This sent the fuel tender down the

other track. If this had been a conventional engine, it would have been on its

side at this point. I assume this derailment could only have happened with the

train backing through the switch.

because

it had a hinge point in two places. The black and white photo at the right shows

the articulation factor saving the day. The switchman threw the track switch before

the engine had completely cleared the switch. This sent the fuel tender down the

other track. If this had been a conventional engine, it would have been on its

side at this point. I assume this derailment could only have happened with the

train backing through the switch.

The

Garrett was like a mule compared to a race horse. They would drag a train through

rugged terrain, but they were not very fast.

We

were around Miwani Sugar Estates east of Kisumu, after being delayed for some

reason, and the lake steamer was waiting for us because we were 90% of the first

class passenger list. So, the engineers opened the Garrett up to fly since this

section of track is the only really straight stretch in the line. We looked down

the train to the engine, and fire was blasting out both sides of the engine. We

clocked the train by timing sign posts, and we were doing all of 54 miles per

hour. Of course, schedules and speed were not the highest importance in African

life-- getting there at all was enough for most people. Again, stiff upper lip,

old chap. I have since learned that the all time record for a Garrett Class 59

was set in France at 81 MPH. I have since revised my accusation that they were

slow.

Train

Amenities

The

trains in Kenya were set up on the European arrangement rather than with Pullman

cars used long ago in the USA. You were assigned to a compartment with three other

people and a door that shut out the world. A narrow hallway ran along the side

of the full length of the car between the compartments and the outside windows.

When it was time to go to sleep, the African steward would come in and pull up

the backs of the seats, and they became top bunks. With we kids seniority dictated

who had to climb up on the top bunk. Seniors never had to climb, but if the seniors

were responsible that meant they did guard duty also.

Each

compartment had its own sink, and passengers took turns in the morning cleaning

up there. The sink had a fold down lid which became a desk during the day. This

arrangement gave passengers opportunity to become very personal in getting to

know each other, or else it made them very edgy about their compartment mates.

It all depended on the temperament of the occupants. Electric fans buzzed trying

to keep the compartment cool, which worked poorly, and in train stations the windows

had to be raised if you didn't want vendors on the platform  yelling

into your windows a menu of all their tasty snacks, like fried corn and beans,

samoosas, jageri, boiled eggs, and all sorts of candy.

yelling

into your windows a menu of all their tasty snacks, like fried corn and beans,

samoosas, jageri, boiled eggs, and all sorts of candy.

One

unique vendor often seen was a fellow with a huge selection of the most obnoxious

vials of perfume and incense. These were for Indians who lived in East Africa.

The Indians were somewhat delinquent in bathing, so they anointed themselves with

these rank nasty perfumes and burned incense to their favorite god, and these

two odors would cast a spell that sent them to Nirvana where body odor is apparently

well received. This sounds politically incorrect I suspect, but this story is

about the real world, not your world laundered by your dear social nanny mentality.

The

trains stopped frequently because there were many stations, and that gave us around

fifteen minutes to get off and wander the platform. Vendors harassed us, and there

were a row of kiosks selling all manner of things. We all liked the PK Pellets

which were Wrigley's chewing gum, now called Chicklets. Many years later I learned

the "PK" was for Mr. Wrigley's first two initials. If your Dad gave

you enough allowance for the trip, you bought a Cadbury's Kit-Kat bar. These were

in Africa long before they were in the USA. There was also soda pop in flavors

never seen outside of Africa. The Indian soda pop makers would think of all manner

of strange names like watermelon, ice cream, peach melba, and the name had nothing

to do with the flavor which was usually vanilla or lime.

One

time several of us boys were wandering up the platform at a stop, and an African

came up to us with some pictures in his hand. He had a strange look on his face.

As we got near he flipped the pictures over, showed us a naked lady, and said,

"Two bob (shillings) for lady picture." We were confused and amazed

at this African. What on earth did he think would happen? We lectured him mightily

on morality, and the poor fellow wandered off in confusion. This was my first

experience dealing with pornography, and I can assure you the vendor had NO business

from Africans.

Take

a walk from the train station in any direction, and some African woman was pounding

out the evening corn meal, eaten at all meals, in a huge wooden mortar, and getting

hot she would throw off her top cloth and be naked to the waist. Two bob for a

dirty picture? None of us understood in the 1950s that the Europeans in Kenya

had already made their mark on the country by paying for this early form of porn.

It was our initiation to the ugly world, and in the heart of Africa at that.

The

trains had a dining and kitchen car. An African steward walked down the hallway

beating on a set of four chimes, bong, bong, bong, playing some tune he invented,

and that meant dinner was served in the dining car. In the 1950s colonial era

they still had silver service with eight to ten pieces of cutlery and huge lumpy

china with the rail company logo on it. The meals were four course, including

soup, then a postage stamp size piece of fish with a slice of lemon, the entree,

and finally dessert and coffee. The fish was the best part. The entree was usually

anything that could be boiled to death, which is classic British form of course.

The entree could also be given some character by drowning it in Worcestershire

sauce. The coffee was powerfully ominous stuff in a tiny cup. The bread served

was dense, VERY dense, but it made good fish bait when soaked in water for a few

seconds and kneaded well. This fish bait was used on the lake steamer later to

fish while in port.

Breakfasts

were started with a shallow bowl of oatmeal that was thin and watery and scarce.

The eggs and bacon were great-- one thing the British do well. Don't order the

sausages-- they are 40% cereal filler. But, the toast was intentionally allowed

to dry and cool before serving until it was hard as a shingle. The British think

hot toast is nasty. Don't ask why please-- I never have learned why. The bitter

marmalade was great, and I often polished off a whole pot because the other kids

did not like it.

The

trains cars had restrooms marked "Eastern Type" and "Western Type".

The Western Type were familiar enough, but the Eastern Type only had a hole in

the floor, raised footprints, and you squatted to use them. They were deadly because

if you dropped a wallet or something of value, it was down the hole and out along

the right of way and long gone. These toilets emptied right out onto the ground.

There was a sign in them reading, "Please do not use the WC while the train

is in the station." And, if you wanted to stand and watch a passenger train

go by out along the right of way, you wanted to stand very far back from the tracks.

The express to flushing was not a train in New York. I am sure modern trains in

Africa have more sanitary arrangements today.

Derailment

and the Aftermath

We

were on our way to school one time, and were approaching Fort Ternan.

Fort

Ternan is a whistle stop and only used if a passenger is waiting there to board

the train. The curve south of the station had nothing odd about it, but the train

stopped very suddenly as we started around the curve. The missionary parent escort

got out and walked to the engine, and he saw that is was skewed on the rails.

It had derailed, and the British engineer and brakeman had been able to stop the

engine before it tumbled on its side.

The

Garrett engines had two huge jacks mounted on the engine with heavy steel brackets,

and they wrestled them off and under the engine. They then jacked and pried with

bars in tiny increments until the front truck wheels were back on the track. The

engineer told us the they had a superstition among themselves that the third time

an engine derailed it would tumble on over. That engine was having its third derailment.

He concluded that because all of us missionary kids were on the train that God

was on our side. He was right.

He

also said that African herd boys had put rocks on the track in a line, from small

to larger, so that the front truck wheels rode up the rocks and fell off the tracks.

The boys had probably sat around the camp fire listening to grandpa tell how he

and his Kipsigis tribal friends had attacked the railroad construction in around

1900, and the boys wanted to see if they could get in one more lick for the tribal

bad attitude.

It

took a long time to get the engine back on the tracks, and then we went on up

grade headed for Lumbwa. Before Lumbwa was a long steep curved bridge which had

been built for the British government by an American bridge builder in about 1897.

It had no side rails in those days, and if you looked out the window there was

nothing to see but the ground far below. I was rather terrified of this bridge

because it seemed very high.

It

took a long time to get the engine back on the tracks, and then we went on up

grade headed for Lumbwa. Before Lumbwa was a long steep curved bridge which had

been built for the British government by an American bridge builder in about 1897.

It had no side rails in those days, and if you looked out the window there was

nothing to see but the ground far below. I was rather terrified of this bridge

because it seemed very high.

The

engineer told us during the derailment event that a train once came down this

bridge out of control. They had gotten going too fast, and the brakes would not

stop the engine. They put the engine in reverse and went through Fort Turnin at

high speed with the drive wheels screaming in reverse at full throttle, smoking

and throwing sparks. The train had jumped the tracks right where our train had

derailed. I always held my breath going along there from then on.

Lumbwa

is named for a ceremony between the Kipsigis tribal leaders and the British railway

officials in 1909 when fighting was called off by the Kipsigis tribe who tried

to stop the building of the railway through their land. A dog was cut in half

and its blood sprinkled around the area. The train station was named Lumbwa (L'umbwa)

at that time. Umbwa is Swahili for dog. You may wonder how very proper

British colonial officials could participate  in

a dog sacrifice to seal a peace treaty. Well, the British were masters of mixing

African culture with British peculiarities so that the natives would understand

the thing.

in

a dog sacrifice to seal a peace treaty. Well, the British were masters of mixing

African culture with British peculiarities so that the natives would understand

the thing.

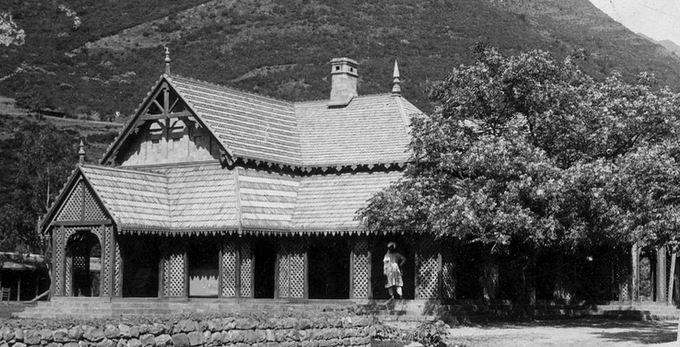

Lumbwa

station was a rambling "dak bungalow" building that wandered all over

the hill side because it had been added onto over and over. The dak bungalow in

the photo was in the hill country of India. The dak at Lumbwa was sided with corrugated

metal painted green. The British colonial masters loved corrugated metal buildings,

but they were terribly hot in the sun, and when it rained the roof roared inside.

It was

way past the noon dining hour when we finally arrived after the derailment at

Lumbwa. We piled out of the train because this was a meal stop for tourists. But,

the African cooks and servers had gone home. They were called back with copious

threats by the Sikh Indian station master, and they put together a strange meal

with the only thing left on hand. Scrambled eggs with strawberry jam in it, and

green beans. Jam on scrambled eggs was most peculiar, but the worst part about

this meal was that they had boiled the green beans in a tin pot that had been

used to hold kerosene. Now folks, I assure you, kerosene is not an alternative

for hollandaise sauce on green beans.

We

got into Nakuru late for the evening meal because of the derailment also, so the

station master arranged for us to walk from the station to the Stagshead Inn in

downtown Nakuru. This was a stuffed shirt privileged class inn for British White

settlers, farmers and itinerant colonial dandies, and a coat and tie were required.

Also, no Africans could eat there in those days.

We

got into Nakuru late for the evening meal because of the derailment also, so the

station master arranged for us to walk from the station to the Stagshead Inn in

downtown Nakuru. This was a stuffed shirt privileged class inn for British White

settlers, farmers and itinerant colonial dandies, and a coat and tie were required.

Also, no Africans could eat there in those days.

Here

is a gathering of colonial dandies somewhere in the Kenya Highlands.

We

all came traipsing in dressed in kaki with no tie of coat, rumpled and weary,

and the poor British elite had to put up with a mob of Yankee brats who were starved.

The food must have been good because I do not remember it. Hey, when you are a

kid growing up in Africa the most notable food is that which tries to crawl away

as you eat it or food that burns the roof off the top of your mouth.

Traveling

During the Mau Mau "Emergency"

Mau

Mau was a rebellion of the Kikuyu tribe against the British from 1952 to 1957.

It was called an "Emergency" by the British colonial masters to conceal

the fact that it was a small war between the British and the Kikuyu tribe. No

other African tribes participated, and the claim by President Obama that his Luo

grandfather took part in the Mau Mau is a lot of rubbish. The Luo tribe hated

the Kikuyu tribe and had nothing to do with Mau Mau. [ The added details here

are free stuff to reward you for reading this. ]

When

it was time to leave the school to go home on the train, we went to the train

station in open stake bed trucks. We traveled through the forests where the Mau

Mau operated, so some of our King's African Rifles African guards came along in

another truck. I believe our departure time was concealed for security reasons,

and there may have been KAR troops in the forest along the way, but we would have

never known that. We were partially sheltered from knowing just how badly the

Mau Mau wanted to kill us kids to terrify the British and Americans living in

Kenya.

We

left Kijabe train station in the afternoon, and we arrived in Nakuru at dusk.

During the Mau Mau trains did not run at night. We slept overnight in Nakuru under

heavy guard. In the morning we woke up to the PA system playing the Weavers singing

on an old 78 RPM recording called "Round the Bay of Mexico" (which I

included here from 1950), and for the life of me I could not connect the Nakuru

train station, surviving the Mau Mau, with waking up to the Weavers telling me

about the Bay of Mexico. As a kid I knew that it was called the Gulf of Mexico,

not the bay. The Weavers were from Greenwich Village in New York-- figures.

Breakfast

was served at the Stagshead Inn mentioned above, and then off down the line for

home.

We

were supposed to keep our heads in the train car, but we wanted to see a Mau Mau

if there were any. Looking back I now marvel that we never had any issues from

the Mau Mau, and I suspect there will be a group of angels in heaven whom we need

to thank for doing their good work for our Father in Heaven by keeping us brats

alive.

Kisumu

Kisumu

is a lake port city on the northeast corner of Lake Victoria and it was the original

western rail terminal point of Kenya, Mombasa on the Indian Ocean being the starting

point. Going to school, we had to leave the steamer at Kisumu, but before doing

so we had about one day in port killing time. The water was shallow, barely giving

the lake steamers enough depth to enter the port. The propellor churned up mud

so badly that the water was a deep chocolate brown. We decided that was where

the RVA staff in charge of our school kitchen got our chocolate milk for Sunday

evening meal. It was supposed to be a treat, but the chocolate powder of British

origin in the 1950s was grainy, and the cook diluted it too much.

Some of us tried our hand at fishing for catfish while in port. We used bananas

or dough balls and a long piece of heavy cord. The trick was to stand nearby,

and when a catfish hit the line, grab it and pull up some slack so we could turn

the fish around when it got to the end of the line. If we did not do that, the

line snapped. If we caught a big one we could sell it to the Luo tribal fishermen

nearby for a couple of shillings. The fish they caught was opened up after cleaning,

laid out flat, and dried on the hot rocks along the lake shore. The smell was

horrendous if a north wind was blowing. I know missionaries who ate that fish

in stew with the hard staple mush made of corn meal. They said it was hard to

get it past your nose, but in the mouth it was delicious. I decided to take their

word for it.

We

also would go downtown Kisumu and cruise the dukas (shops) owned by the Indians.

We were away from home AND school, so some tricks were in order. I will discuss

the tricks we played on the Indian merchants when I talk about the lake steamers

and Kisumu port in that section.

Aside

from victimizing these poor fellows, we loved the Indian sweets shops. They had

amazing varieties of home made sweets that were well worth the investment. Also,

the carry-out food shops were a favorite. They had samosas with green fresh chutney,

pakora, and other deep fried treats. A cone of jaggery was always fun. Jaggery

is a cone of molded cake sugar made from palm tree fruit. It is black as pitch

with lots of flavor, and possibly some added biology to haunt a person later.

Aside

from victimizing these poor fellows, we loved the Indian sweets shops. They had

amazing varieties of home made sweets that were well worth the investment. Also,

the carry-out food shops were a favorite. They had samosas with green fresh chutney,

pakora, and other deep fried treats. A cone of jaggery was always fun. Jaggery

is a cone of molded cake sugar made from palm tree fruit. It is black as pitch

with lots of flavor, and possibly some added biology to haunt a person later.

It

is some sort of tribute to the Indian zeal that makes brightly colored food appear

in the most drab settings.

You

may wonder about the risk of eating these things in a tropical country. We did

too, but we also were a bit cavalier about the risk. I estimate I had amoebic

dysentery about ten times during my years in Africa. The cure worked every time.

Later, as missionaries, my wife and I would eat out in Nairobi or Eldoret and

go home and take Tetracycline for desert as a prophylactic.

While

in Kisumu a missionary family, the Capens, often invited all of us to their home

for home baked cookies or homemade donuts and hot chocolate. They were missionaries

of the African Inland Mission stationed in the town of Kisumu. That was really

a treat, but we had to walk to their home and back to the lake steamer and be

careful not to miss the boat leaving.

The

train cars were backed down to the dock where the lake steamer was tied up, and

the engineer would go very slow because he could not see where the cars were going.

Any pedestrians must be allowed to get out of the way. Gary Lowspire loved to

show his great prowess for danger by hanging off the side of the train as it went

along. There was a gate which the train had to pass through which was closed when

not in use for security. It was very close to the train cars, and Gary one time

miss calculated and got clobbered badly by the iron gate. He moaned a while and

then told us it was really fun. Hmmm

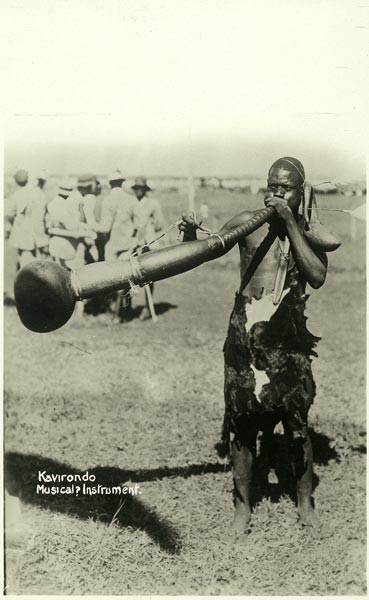

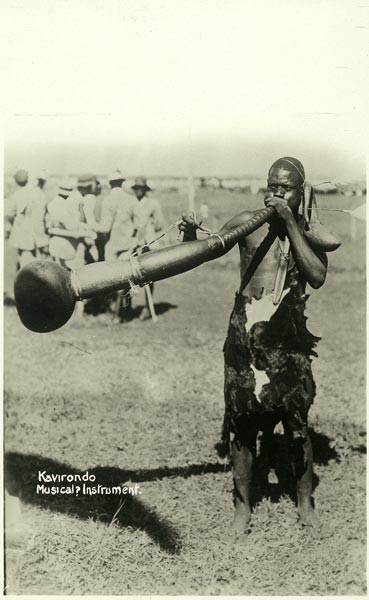

One

of the most colorful things we always enjoyed was an old Luo tribesman who had

a huge horn almost as tall as he was. It terminated at ground level in a huge

gourd. He blew into the mouthpiece, and he made several very low tones and shuffled

his feet which had bells on them. It was quite a concert, and we tossed him coins

to keep him going. The old fellow had done this for tourists for years, and his

cheeks ballooned out so badly we wondered if they might burst. The photo at the

left may have been that very man for the caption says this was taken in Kavirando

where Kisumu is located. This photo would have been when he was much younger than

when we saw him.

One

of the most colorful things we always enjoyed was an old Luo tribesman who had

a huge horn almost as tall as he was. It terminated at ground level in a huge

gourd. He blew into the mouthpiece, and he made several very low tones and shuffled

his feet which had bells on them. It was quite a concert, and we tossed him coins

to keep him going. The old fellow had done this for tourists for years, and his

cheeks ballooned out so badly we wondered if they might burst. The photo at the

left may have been that very man for the caption says this was taken in Kavirando

where Kisumu is located. This photo would have been when he was much younger than

when we saw him.

We

will return to more in Kisumu a little later.

Tricks

and Survival

Any

time you send a mob of individualistic highly active missionary's kids on down

the line, something is going to happen, and it may not be in the model of the

ideal politically correct school boy in your Weekly Reader.

Let

me tell you about Gary Lowspire. [ The prudent who know this story will be able

to translate Lowspire to recall who this really is. ] Gary's Dad was full of fire

and passion for the Gospel and a life well lived. So, it should have been obvious

that his son Gary might be the same. The problem was, Gary had not yet "put

away childish things," as the Apostle Paul did, and become a man. None of

us had, though we were trying. And, who expects young men to hurry this process

anyway?

So,

Gary made the best of his youth. When we were traveling on the HMSS Usoga on Lake

Victoria one time, on our way to school, we were thrown together with British

boys on their way to Saint Mary's Catholic boys secondary boarding school in Nairobi.

There was always a bit of tension at such times because the British colonial world

fostered a sort of static tension between Protestant and Catholic officials, missionaries,

and professionals. Everyone pretended to live above it, but it was always lurking

beneath the surface.

Well,

Gary saw a chance to make a point. At meal time we Protestant kids sat on one

side of the dining room, and the Catholic boys on the other side. At the first

meal, Gary walked in and sat at a table with the Catholic boys. He made up some

tale about his parents being Catholic and in some US social agency. He claimed

he was going to Saint Mary's school with the boys, and he eventually convinced

them.

Well,

Gary saw a chance to make a point. At meal time we Protestant kids sat on one

side of the dining room, and the Catholic boys on the other side. At the first

meal, Gary walked in and sat at a table with the Catholic boys. He made up some

tale about his parents being Catholic and in some US social agency. He claimed

he was going to Saint Mary's school with the boys, and he eventually convinced

them.

But,

when the meal was served, which the waiters served in formal fashion, Gary filled

his plate and waited until all the boys at his table had all been served. They

all bowed and crossed themselves...... except Gary. He bowed his head and prayed,

"Mary, Mary, quite contrary, how does your garden grow?"

He

got no further. The other boys cried foul, and accused him of playing a trick

on them. Gary admitted it at once and got up, picked up his plate, and started

across the room to our side. The Saint Mary's boys told Gary to stay since they

thought his trick was worthy of their own prankish style. Gary declined, though

I think he regretted it later.

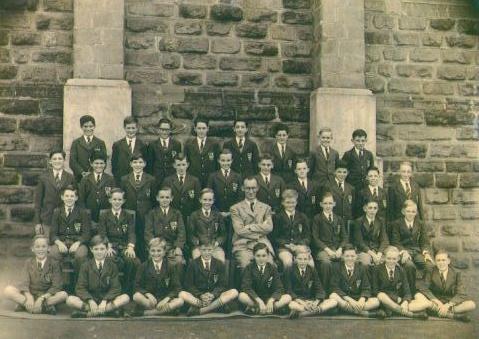

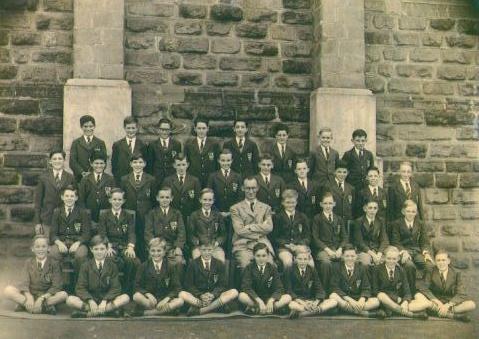

The

photo above at the right is the Saint Mary's class that we encountered,

among

whom are those who traveled from Tanzania.

Well,

that was not the end of the story. The

Saint Mary's boys spent the rest of the trip on the lake steamer jabbing at us

and we at them. There was an understanding that we must not escalate it to anything

really nasty, but things evolve, do they not?

When

we boarded the train at Kisumu for the trip up country to our school, there was

what Henry Kissinger used to call, "an escalation of hostilities." We

all settled in to our four person compartments, but soon "Thump thump"

on the door and the patter of feet. We knew who it was. This went on all afternoon,

and then the African steward came by tapping out a tune on his four note marimba,

the call to the evening meal in the dining car.

We

all went to eat, and when Gary came back he tucked a whole loaf of bread under

his jacket. The bread was not sliced until just before serving in order to keep

it fresh in the tropics. Somehow Gary convinced the steward that he needed a whole

loaf of bread. Once we were back in our compartment, we waited for the inevitable

"thump thump."

It

came. Gary opened the desk top of the sink used for freshening up in the morning.

He filled the sink with water, submerged the loaf of bread in it, and checked

the Saint Mary's boys' compartment. They were in the next compartment down from

us, and they had their window open, as we all did, for fresh air. Gary picked

up the well soaked loaf of bread very gingerly lest it disintegrate, he leaned

way too far out the window for safety, and our heroic champion in battle, Gary,

lobbed that water soaked loaf of Eliot's bakery bread through the boys' window.

We

heard some British English that is seldom heard in civilized Catholic company,

and after a while we heard a timid, "tap tap" on our door. Gary opened

the door very carefully part way, and a Saint Mary's boy, with bits of bread on

his lovely red tunic, said, "I say, blokes, could we have off with this?"

Never

in the annals of warfare have two adversaries come to terms so quickly and cordially.

We boys had just been discussing what the Saint Mary's boys might do to us to

raise the level of hostilities. So, we were only too pleased to accept their terms

of surrender.

For

the rest of the trip we went out of our way to be jolly and kind with the Saint

Mary's boys lest the "just and durable peace" turn sour. I would love

to hear from a Saint Mary's boy, who by now is retired, and talk about old times.

If you are ever in Texas, stop by, and we will break bread together. Well, unsoaked

bread actually.

SEND

MAIL

The

Train Culture

The

trains used a European style of coach. There was an aisle down one side of the

coach, and the compartments were entered off of the aisle. The compartments had

seats with high backs for the daytime, and at night the high back folded up to

make a top bunk. Someone had to climb up to sleep. Seniority bought privileges

in our thinking, so the seniors got the lower bunks while the "titchies"

(little kids) got to climb. This was sometimes reversed out of mercy for grade

schoolers lest they fall trying to go to the restroom in the night.

There

were many station stops. This is typical of the colonial era and the present Third

World era. This is because the trains are far more important to travel in the

Third World where people cannot afford to own automobiles. The bus system was

unpredictable in the rainy season, and there was no moving violation enforcement

in Kenya long ago on the highways, so busses would race to get to passenger pick

up points, and deadly head-on collisions were not uncommon.

This

brings up safety.

First,

the trains moved slow compared to Europe and the USA. We clocked the train by

mile posts one time at about 54 MPH. This was high speed on the EAR&H Railway,

and this case was only because we were running late, and the lake steamer would

be held up until we arrived because we were the whole first class passenger list.

Second,

the trains were very safe because the EAR&H had a fool proof safety system

which they inherited from England. The semaphores were controlled by a telegraph

system. The semaphore would not move all clear for a through train until a key

was turned in a huge slot in a massive red box by the station master and dropped

on the correct side. The key was acquired from the engineer by the station master

in a hoop pouch as the train moved through the station. The station master then

ran inside the station and slammed the key into the slot and turned it and dropped

it. The station master also would remove a key from another machine, put it into

a hoop pouch, and hand it off to the engineer as the train passed through. This

key was then carried to the next station by the engineer and handed off to the

next station master. Dropping a key was a national emergency, especially if the

engineer missed catching it, because everything came to a grinding stop, and that

could cause backups in both directions.

This

was cumbersome compared to our present computerized system, but ironically, it

was even safer then computers. The only way a train could meet another train in

a collision would be if some engineer or station master went mad and decided to

make havoc on purpose. In the colonial world people just do not make havoc on

purpose. Any compulsion to mad behavior was reserved for the next sun downer (cocktail

party at sun down), and a couple of gin and tonics would usually cure the crazies.

Now, being stuck on stupid, that is another matter. So the key system even eliminated

stupid.

A

train became an express only if it was totally maxed out with passengers or when

some dignitaries were on board. We had the distinct honor, as White race school

brats, of causing our train ride to be a partial express. We felt very important

as we roared through several stations along the line. "Wait for the next

train, peasant."

I

do not recall anyone ever being left behind except Don Hoover, my brother-in-law.

The engineers were under orders to see that every one of us got to our destination,

so the train might be delayed for someone arriving late. And, what about Don Hoover?

The night we were to leave the train station, Kijabe, near the school, we all

stayed awake and played games. We had to board the train at 2 AM. One time Don

thought he would take a short nap. All of our beds had been stripped and all of

our personal effects packed in steamer trunks. Don found two mattresses, sandwiched

himself between them, and went off into lala land. We all loaded up on two open

bed stake trucks and headed for the train station. No one missed Don because we

thought he was in the other truck.

The

Principal, Herb Downing, did a head count, and someone was missing. Suddenly,

we all figured out that Don was missing. We boarded the train, and Herb Downing

rushed back to the school, loaded Don Hoover into his Ford station wagon (a luxury

car in those days in Kenya), and he raced the train to the next station, Nakuru.

He made it in time, and Don was a bit of a celebrity.

When

the train stopped in stations we would get off and walk around the platform and

barter for baskets and curios to take home to Mom, or we would engage some African

dandy in conversation and hone up our Swahili. It feels good to be a colonial

Anglo Saxon brat because even African politicians and chiefs would stop and converse

with us. They had mixed motives of course. They might get some juicy bit of intelligence

from a missionary kid who talks too much, but mostly, they too wanted to hone

up their language skills and see if their English was up to par.

When

the train stopped in stations we would get off and walk around the platform and

barter for baskets and curios to take home to Mom, or we would engage some African

dandy in conversation and hone up our Swahili. It feels good to be a colonial

Anglo Saxon brat because even African politicians and chiefs would stop and converse

with us. They had mixed motives of course. They might get some juicy bit of intelligence

from a missionary kid who talks too much, but mostly, they too wanted to hone

up their language skills and see if their English was up to par.

The

brave and foolish among us would pop into an Indian duka (shop) and buy samosas

or jalebis. The dysentery germs were too small to see, so we did not worry. For

the cautious, a banana or boiled egg was safer. The Lou women cooked corn and

beans until they were slightly dry, and you could eat them like peanuts. More

on snack concerns later.

We

met a group of students from Makerere College one time at a station stop, and

we got them to talking. They were strutting about feeling very important because

they had reached the pinnacle of education for all of central Africa. Makerere

College was an extension school of Oxford in England. Well, we missionary brats

felt we were at least their equals since we were in a well known and exceptional

Secondary School, AND, we were Anglo Saxons to boot. So, we started trying to

tangle them up in their words. They caught us, and one of they indignantly said,

"Don't abuse me, I am from Makerere College." From then on, we often

used that phrase on each other in the dorm.

We

always had a missionary escort along, both going to or coming from school. These

were almost always parents of some kids traveling, and their kids had the distinct

disadvantage of having to behave themselves better than the rest of us. The missionary

escort had to make sure we and all of out trunks were on the train, he had to

make sure every kid was on the train when it left a station, and he had to pull

the chain to stop the train if a kid was missing. The chain somehow ran the full

length of the train, and there were pull points in each car. There was a notice

on the red opening, "To stop the train, pull the chain downwards."

The

escort also had to collect the four gallon tins of peanut butter in Musoma from

the Mennonite Missionary peanut farm project. That was top priority, for we kids

loved Mennonite peanut butter. This was collected in the port of Musoma which

was a port the lake steamer always visited. The fear of losing a kid kept most

escorts from sleeping well, and when we arrived at school the escort usually disappeared

for a day to catch up on sleep. One trip Frank (Pop) Manning was our escort, and

he was exhausted when we arrived at school. A couple of the boys learned where

the school had provided him a bunk for a day, and they went there before Pop Manning

got there and short sheeted his bed. Pop Manning never figured it out and rammed

his legs through the sheet, putting two holes in it, and slept like a baby for

hours.

Short

sheeting the bed is the art of folding the bottom sheet back at the half way point

and then making it appear that it is both sheets. The surprise is startling when

a person tries to slide his feet into bed and only seems to have half a bed.

The

rail line was famous for its steep grades. This was because the train had to climb

a significant grade to the Highlands town of Limuru about twenty miles from Nairobi.

The train then went over the top and dropped down to the Rift Valley floor on

an even steeper escarpment. Then another steep grade was required out of Nakuru,

and finally a long steady drop to the Lake Victoria. This meant we spent about

half the trip trundling along at as little as twenty MPH, and then we worried

whether the engineer was smart enough to avoid a run away doing back down. Run

aways did happen.

The

rail line was famous for its steep grades. This was because the train had to climb

a significant grade to the Highlands town of Limuru about twenty miles from Nairobi.

The train then went over the top and dropped down to the Rift Valley floor on

an even steeper escarpment. Then another steep grade was required out of Nakuru,

and finally a long steady drop to the Lake Victoria. This meant we spent about

half the trip trundling along at as little as twenty MPH, and then we worried

whether the engineer was smart enough to avoid a run away doing back down. Run

aways did happen.

The

original line was so confusing to the engineers in 1903 that they broke the line

near our school, winched the train cars on trolleys up or down a short section

of track at about 45 degrees, remade the train on the Rift Valley floor, and another

engine hauled the train to Kisumu. The photo at the left shows an engine being

lowered down the make shift trolley system.

After

the First World War the grade was redesigned without the winching innovation.

But, there was concern that in the event of war bridges could be bombed and stop

all transportation of troops and goods to the lake in inland areas. In such a

case, Germany could easily take central Africa. So there were almost no bridges

of tunnels. Instead, there were extremely deep cuts and massive fills. The diggings

of the cuts were simply passed forward to the inevitable fill immediately after

a cut. So, there were almost no issues of failing bridges and tunnel cave ins.

After

the First World War the grade was redesigned without the winching innovation.

But, there was concern that in the event of war bridges could be bombed and stop

all transportation of troops and goods to the lake in inland areas. In such a

case, Germany could easily take central Africa. So there were almost no bridges

of tunnels. Instead, there were extremely deep cuts and massive fills. The diggings

of the cuts were simply passed forward to the inevitable fill immediately after

a cut. So, there were almost no issues of failing bridges and tunnel cave ins.

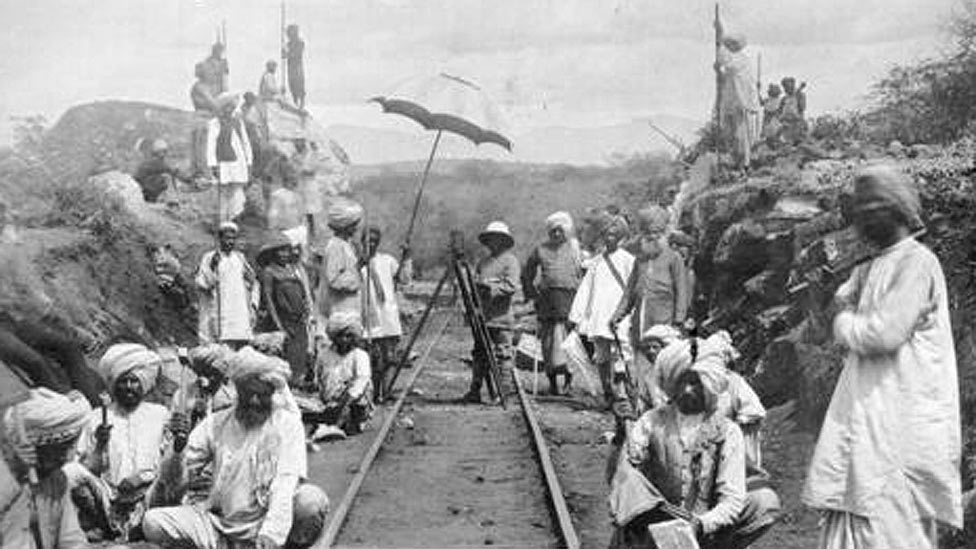

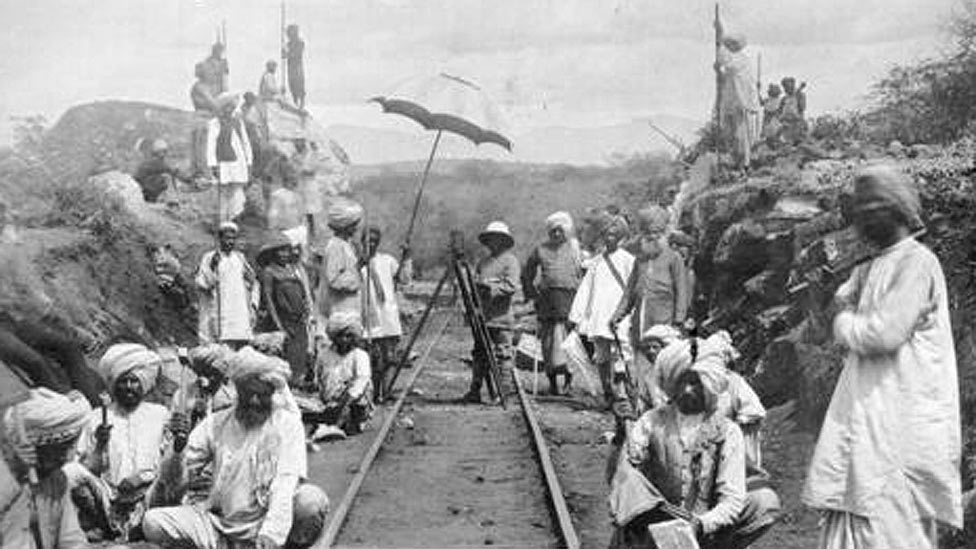

All

of this moving of massive amounts of soil and rock was done by work crews like

the one in the photo using "karais" which were huge metal bowls about

two feet in diameter. They were carried on the head of the African and Indian

workers.

The

railway passed along the upper property line of the Kijabe Mission station which

included about 700 acres, and our school was on this station. We kids had some

good times along the tracks. I loved to hike in the forest above the school which

was dense and moderately dangerous due to leopards and snakes. Moderate danger

is something the nanny state of this present world tries to eliminate, at least

natural danger. Instead, kids in our modern world are in danger of getting hearing

loss from overly loud boom boxes, and they are at risk of being sexually abused

at home, at school, and at church. And, the people who claim to be protecting

them are the most dangerous stalkers. I encourage you to take your kids to the

country where they have to only deal with snakes and the beasts of the field.

When

hiking, we seldom got lost. The hills and forest above the school were above the

railway, so if we did get lost, we could simply go down hill until we reached

the rails, determine the grade, and walk right or left accordingly. I got a buzz

out of getting myself lost and using this technique to get back to the school.

If done correctly, a kid could honestly claim he was lost if he did not show up

when expected. Getting lost was a regular past time.

I

was in about ninth grade when Herbie Lyon and Karl Uline, upper classmen, invited

me to go on a hike. I was delighted. It was not common for the "big guys"

to take us younger kids along on a hike. They then took me to a point far up in

the forest, and, claiming they needed to empty their bladders, walked a distance

away while I tried to be correct and look the other way. They then disappeared.

By the

time I figured out that they had abandoned me, and after some brief panic, I decided

to reward them for their treachery. I fled the other direction, downhill, as quietly

as possible. I knew where there was a five foot diameter culvert under a high

railway fill. It was very long, and water trickled down it all the time, and it

was a great place for snakes. I cast caution to the wind, and in my mad frenzy

to punish Herbie and Karl, I found the culvert and tracked through it with fear

and trembling lest a snake bite me. At the other end was the road from the African

town of Kijabe to the school. I took this road at a trot and got back to the school

and hung out in obscure places. The only part that really made me tremble was

that as I exited the culvert I saw the slashes on a tree nearby where a leopard

had sharpened his claws.

Meanwhile,

Herbie and Karl had second thoughts. They had visions of me falling over a cliff,

or being attacked by a leopard, and they went looking for me in the forest. They

spent the rest of the afternoon trying to find me and came back to school terrified

because they had not found me. They came to supper wide eyed and in a near panic,

and when I walked in they were taken with both rage and massive relief. What joy

it gave me to see them struggling between wanting to strangle me and hug me. "Where

were you, you rotter?" "Oh, I just walked back to the school."

They will only now be learning how I did this to them. Herbie, you owe me pie

and coffee some time.

Another

past time for us boys along the tracks was to throw big rocks from the top of

a cut onto the passing empty flat cars and hear the BONG as they hit. Scores were

kept, and competition developed. One day, I had not hit one flat car, and as the

caboose came along, I threw a huge rock. It hit dead center on roof of the caboose

and sunk deep into the insulation used to keep the caboose from becoming an oven.

The Sikh conductor popped his head out of the window, saw us kids standing up

on the top of the cut, and we had a short lesson in Gujarati words not usually

used in mixed company. Months later, when we stood and watched a train go by below,

someone might say, "Hey Steve, there goes your rock." My rock-- what

a distinction to know that my rock had been all over East Africa. I suspect one

day, years later, as they were sending an old caboose to the scrap yard, some

employee wondered at the rock and how it got there. Mawe gani hii?

We

later came up with an idea for a stunt that would have been interesting. We wanted

to make a random sort of round cage of wattle tree branches, and then cover it

with brown paper with glue. We would roll it in dirt before the glue dried and

make the thing look like a huge boulder. We would put it on the tracks where the

train downhill came over a rise so that the engineer would see it a bit suddenly.

As he set the brakes, and just before the train hit the boulder, we would jerk

the boulder off the tracks, with a string tied to the fake boulder, into a nearby

ravine where we would hide. We imagined that the engineer's facial expressions

would be worth all the trouble.

But

in a rare fit of consideration for humanity, we decided that if the train coming

were a passenger train a lot of people could get hurt being flung to the floor

or spill their hot tea when the brakes were set into emergency. Alas, some great

inspirations must be set aside in difference to the masses.

With

all the possibilities for distraction in the Kenya Highlands, our tolerance of

boredom was almost zero. So, on a day when such boredom set in like a thick cloud,

we kids went and secured several loaves of bread from the pantry. The bread was

not sliced until it was used. We took the loaves of bread and headed for the railway

tracks. We dipped them in a small creek nearby, and went and stood along the tracks

in a line.

Along

came a tourist special full of Anglo Saxons looking for adventure in Darkest Africa.

Why not give them an experience to really remember?

These

special trains were filled with only first class passengers from Europe who were

using the railway to tour Kenya. They had a tour guide book which told of sights

to watch for along the railway, and there was a lovely entry describing the self-sacrificing

humanitarian work of Kijabe Mission Station and the special school for missionary

kids there. As the train came along, the tourists sat gazing through the eucalyptus

trees at the mission-- loving pious smiles on their faces-- admiring the great

philanthropic works of the White race just down the hillside.

Also,

they saw a line of very special Anglo Saxon school boys lined up along the tracks

with one hand behind their back, the other waving, and smiling sweetly like the

young choir boys in Westminster Abby. At the right instant, these boys all launched

their loaves of water logged bread, casting their bread upon the tourists. They

must have had a story to tell back in the UK at the next cocktail party. Far from

being attacked by the Lions of Tsavo, they had been attacked by the bread throwers

of the Kiambu jungles. I suppose a complaint was lodged with the colonial authorities

in Nairobi, but these authorities had their own sons in the Prince of Wales boarding

school in Nairobi, and they would probably only be too thankful it was not their

own boys up along the tracks.

Only

a rail buff can understand the affection some of us have for "our train."

Perhaps

the most benign stunt we played was to lay a ten cent copper coin on the track,

sometimes with a piece of tape, and the train wheels would flatten it as it passed.

This was later handed to an Indian merchant to cause confusion. The coin was much

larger than the original, but usually there was enough of the engraving left to

tell it was a ten cent copper. The Indian merchant would complain, and we would

reason with him that it was indeed still a ten cent piece-- just suffering from

a bit of inflation.

One

day Bob C and I decided it would be fun to butter the rails for the up bound freight

train. The grade was so steep that if the rails were the least bit damp, the drive

wheels would slip and spin out. Sanders were often in use, but they did not always

solve the problem, so the Sikh engineers nursed their throttles very carefully.

Bob and

I appropriated a pound of butter from the kitchen pantry, and we headed for the

tracks. We waited until the downhill train passed, and then we smeared the butter

on both tracks as far as it would last. We then went up the hill nearby and hid

in the bushes and waited for Mr. Singh to come along with his train. The freight

was the usual double header (two engines) with an engineer in each engine. They

were doing a fantastic job of keeping up their momentum without quite enough throttle

to cause the wheels to spin out.

We

speculated that we did not have nearly enough butter, and we fully expected the

train to roll right over the spot and keep going.

Alas,

the freight came steaming stoutly along and hit the buttered section. The wheels

instantly broke free and spun up so fast that it scared us. The engineers stopped

the train and got down out of their cabs to inspect the problem. They may have

thought some part had broken in the linkage. Alas, they soon saw the butter shining

on the rails, and then they both took turns filling the air blue with Gujarati

words not found in your Cambridge English to Gujarati dictionary. Then they rustled

up rags out of the cab and started wiping down the drive wheels and tracks. Bob

and I began to laugh until we had the bushes shaking where we were hiding. The

two engineers turned and saw the bushes rocking about and figured out where the

butter came from. We then received our second lesson in Gujarati that day.

So,

you can see that the railway was deeply part of our school days culture. We did

things along those tracks then which would cause a national emergency to be declared

today. The nanny state today leaves no room for growing up in a sane manner. This,

I must admit, is in the broadest definition of the word sane.

Now,

if any of you kids at Rift Valley Academy today are reading here, understand something

please. You may become inspired to try some of these tricks. But, the world has

changed, and the nanny mind set is now all around the world. This mind set is

something exported from America by Liberals who are terrified that the masses

at large in this world may run wild and hurt themselves or upset Nirvana. So,

some risk is involved if you try these tricks. You may be followed to your room

by agents of the New World Order (staff members) and put on restriction for a

while.

These

engines, when freshened up, were authoritative and classy to look at. Nothing

said, "The British are coming" like a Garrett steam engine. They were

driven by both White British engineers and Sikhs from India. The Sikhs were very

clever at anything mechanical, and they were obsessive about keeping rules and

polishing their toys. Other Indians were great merchants and financial gurus,

but the Sikhs were the only ones to drive a train and make us feel safe.

These

engines, when freshened up, were authoritative and classy to look at. Nothing

said, "The British are coming" like a Garrett steam engine. They were

driven by both White British engineers and Sikhs from India. The Sikhs were very

clever at anything mechanical, and they were obsessive about keeping rules and

polishing their toys. Other Indians were great merchants and financial gurus,

but the Sikhs were the only ones to drive a train and make us feel safe. because

it had a hinge point in two places. The black and white photo at the right shows

the articulation factor saving the day. The switchman threw the track switch before

the engine had completely cleared the switch. This sent the fuel tender down the

other track. If this had been a conventional engine, it would have been on its

side at this point. I assume this derailment could only have happened with the

train backing through the switch.

because

it had a hinge point in two places. The black and white photo at the right shows

the articulation factor saving the day. The switchman threw the track switch before

the engine had completely cleared the switch. This sent the fuel tender down the

other track. If this had been a conventional engine, it would have been on its

side at this point. I assume this derailment could only have happened with the

train backing through the switch. yelling

into your windows a menu of all their tasty snacks, like fried corn and beans,

samoosas, jageri, boiled eggs, and all sorts of candy.

yelling

into your windows a menu of all their tasty snacks, like fried corn and beans,

samoosas, jageri, boiled eggs, and all sorts of candy.  It

took a long time to get the engine back on the tracks, and then we went on up

grade headed for Lumbwa. Before Lumbwa was a long steep curved bridge which had

been built for the British government by an American bridge builder in about 1897.

It had no side rails in those days, and if you looked out the window there was

nothing to see but the ground far below. I was rather terrified of this bridge

because it seemed very high.

It

took a long time to get the engine back on the tracks, and then we went on up

grade headed for Lumbwa. Before Lumbwa was a long steep curved bridge which had

been built for the British government by an American bridge builder in about 1897.

It had no side rails in those days, and if you looked out the window there was

nothing to see but the ground far below. I was rather terrified of this bridge

because it seemed very high.  Aside

from victimizing these poor fellows, we loved the Indian sweets shops. They had

amazing varieties of home made sweets that were well worth the investment. Also,

the carry-out food shops were a favorite. They had samosas with green fresh chutney,

pakora, and other deep fried treats. A cone of jaggery was always fun. Jaggery

is a cone of molded cake sugar made from palm tree fruit. It is black as pitch

with lots of flavor, and possibly some added biology to haunt a person later.

Aside

from victimizing these poor fellows, we loved the Indian sweets shops. They had

amazing varieties of home made sweets that were well worth the investment. Also,

the carry-out food shops were a favorite. They had samosas with green fresh chutney,

pakora, and other deep fried treats. A cone of jaggery was always fun. Jaggery

is a cone of molded cake sugar made from palm tree fruit. It is black as pitch

with lots of flavor, and possibly some added biology to haunt a person later. One

of the most colorful things we always enjoyed was an old Luo tribesman who had

a huge horn almost as tall as he was. It terminated at ground level in a huge

gourd. He blew into the mouthpiece, and he made several very low tones and shuffled

his feet which had bells on them. It was quite a concert, and we tossed him coins

to keep him going. The old fellow had done this for tourists for years, and his

cheeks ballooned out so badly we wondered if they might burst. The photo at the

left may have been that very man for the caption says this was taken in Kavirando

where Kisumu is located. This photo would have been when he was much younger than

when we saw him.

One

of the most colorful things we always enjoyed was an old Luo tribesman who had

a huge horn almost as tall as he was. It terminated at ground level in a huge

gourd. He blew into the mouthpiece, and he made several very low tones and shuffled

his feet which had bells on them. It was quite a concert, and we tossed him coins

to keep him going. The old fellow had done this for tourists for years, and his

cheeks ballooned out so badly we wondered if they might burst. The photo at the

left may have been that very man for the caption says this was taken in Kavirando

where Kisumu is located. This photo would have been when he was much younger than

when we saw him.  Well,

Gary saw a chance to make a point. At meal time we Protestant kids sat on one

side of the dining room, and the Catholic boys on the other side. At the first

meal, Gary walked in and sat at a table with the Catholic boys. He made up some

tale about his parents being Catholic and in some US social agency. He claimed

he was going to Saint Mary's school with the boys, and he eventually convinced

them.

Well,

Gary saw a chance to make a point. At meal time we Protestant kids sat on one

side of the dining room, and the Catholic boys on the other side. At the first

meal, Gary walked in and sat at a table with the Catholic boys. He made up some

tale about his parents being Catholic and in some US social agency. He claimed

he was going to Saint Mary's school with the boys, and he eventually convinced

them.  When

the train stopped in stations we would get off and walk around the platform and

barter for baskets and curios to take home to Mom, or we would engage some African

dandy in conversation and hone up our Swahili. It feels good to be a colonial

Anglo Saxon brat because even African politicians and chiefs would stop and converse

with us. They had mixed motives of course. They might get some juicy bit of intelligence

from a missionary kid who talks too much, but mostly, they too wanted to hone

up their language skills and see if their English was up to par.

When

the train stopped in stations we would get off and walk around the platform and

barter for baskets and curios to take home to Mom, or we would engage some African

dandy in conversation and hone up our Swahili. It feels good to be a colonial

Anglo Saxon brat because even African politicians and chiefs would stop and converse

with us. They had mixed motives of course. They might get some juicy bit of intelligence

from a missionary kid who talks too much, but mostly, they too wanted to hone

up their language skills and see if their English was up to par.  The

rail line was famous for its steep grades. This was because the train had to climb

a significant grade to the Highlands town of Limuru about twenty miles from Nairobi.

The train then went over the top and dropped down to the Rift Valley floor on

an even steeper escarpment. Then another steep grade was required out of Nakuru,

and finally a long steady drop to the Lake Victoria. This meant we spent about

half the trip trundling along at as little as twenty MPH, and then we worried

whether the engineer was smart enough to avoid a run away doing back down. Run

aways did happen.

The

rail line was famous for its steep grades. This was because the train had to climb

a significant grade to the Highlands town of Limuru about twenty miles from Nairobi.

The train then went over the top and dropped down to the Rift Valley floor on

an even steeper escarpment. Then another steep grade was required out of Nakuru,

and finally a long steady drop to the Lake Victoria. This meant we spent about

half the trip trundling along at as little as twenty MPH, and then we worried

whether the engineer was smart enough to avoid a run away doing back down. Run

aways did happen. After

the First World War the grade was redesigned without the winching innovation.

But, there was concern that in the event of war bridges could be bombed and stop

all transportation of troops and goods to the lake in inland areas. In such a

case, Germany could easily take central Africa. So there were almost no bridges

of tunnels. Instead, there were extremely deep cuts and massive fills. The diggings

of the cuts were simply passed forward to the inevitable fill immediately after

a cut. So, there were almost no issues of failing bridges and tunnel cave ins.

After

the First World War the grade was redesigned without the winching innovation.

But, there was concern that in the event of war bridges could be bombed and stop

all transportation of troops and goods to the lake in inland areas. In such a

case, Germany could easily take central Africa. So there were almost no bridges

of tunnels. Instead, there were extremely deep cuts and massive fills. The diggings

of the cuts were simply passed forward to the inevitable fill immediately after

a cut. So, there were almost no issues of failing bridges and tunnel cave ins.